Fine points of introductions(引言的细节)-Why a story?(为何是个故事?)-金字塔原理

2024-11-14

原文

Fine points of introductions

As we saw in How to Build a Pyramid Structure, thinking through the introduction is the key step in discovering the ideas that must be presented in a document. By summarizing what the reader already knows, the introduction establishes the relevance of the question to which your document will give him the answer. You can then devote your energies to answering it.

However, actually finding the structure of the introduction can be a relatively complex and time-consuming activity. To this end, you may want a more comprehensive understanding of the theory and nature of initial introductions than was given earlier. You will also want some insight into the nature of the introductory comments needed at each of the key structural points in the body of the document.

Initial introductions

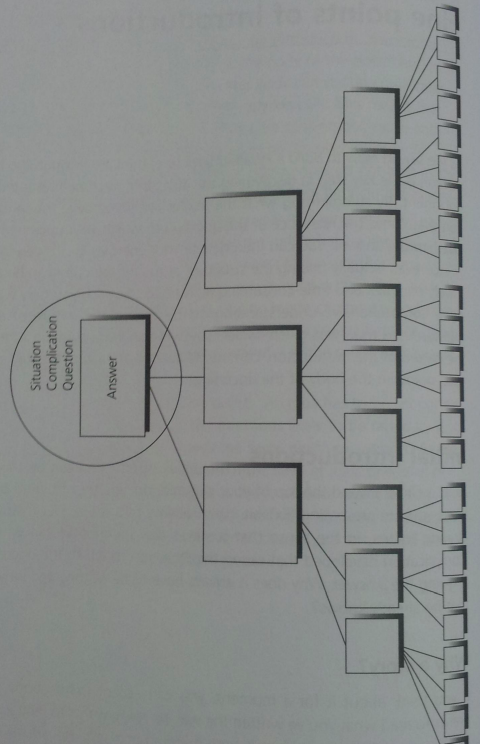

The initial introduction can be thought of as a circle around the top of your pyramid, outside the structure of the ideas you are presenting (Exhibit 10). It always tells the reader a story he already knows, in the sense that it states the Situation within which a Complication developed that raised the Question to which the document is giving the Answer. Why does it always have to be a story, and why one that he already knows?

翻译

引言的细节

如同在《如何构建金字塔结构》中所述,思考引言是发现文档中必须呈现的想法的关键步骤。通过总结读者已经知道的内容,引言建立了问题的相关性,而你的文档将为此提供答案。这样,你就可以将精力集中在解答上。

然而,实际找到引言的结构可能是一个相对复杂且耗时的活动。为此,你可能需要比之前所提到的更全面地理解初始引言的理论和本质。你还需要对文档主体中每个关键结构点所需的引言性评论有一些洞见。

初始引言

初始引言可以被视为环绕在金字塔顶部的一个圆圈,位于你所呈现的想法结构之外(见附件10)。它总是向读者讲述一个他已经知道的故事,具体来说,它陈述了一个情境,在该情境中产生了一个复杂情况,从而引发了问题,而文档则为此提供答案。为什么总是要讲述一个故事?为什么是一个读者已经知道的故事?

原文

Why a story?

If you think about it for a moment, you can accept that nobody really wants to read what you’ve written the way he really wants to read a novel that everyone has assured him is both gripping and sexy. He already has a multitude of jumbled and unrelated thoughts in his head, most of which are on other subjects, and all of which are very dear and interesting to him. To push these thoughts aside and concentrate only on the information you present, with no prior conviction of its interest to him, demands real effort. He will be pleased to make that effort only if there is a compelling enticement for him to do so.

Even if he is quite eager to know what your document contains, and convinced of its interest, he must still make the effort to push aside his other thoughts and concentrate on what you’re saying. All of us have had the experience of reading a page and a half of something and suddenly realizing that we haven’t comprehended a word. It’s because we didn’t push aside what was already in our heads.

Consequently, you want to offer the reader a device that will make it easy for him to push his other thoughts aside and concentrate only on what you’re saying. A foolproof device of this sort is the lure of an unfinished story. For example, suppose I say to you:

“Two Irishmen met on a bridge at midnight in a strange city...”

I have your interest actively engaged for the moment, despite whatever else you may have been thinking about before you read the words. I have riveted your mind to a specific time and place, and I can effectively control where it goes by focusing it on what the two Irishmen said or did, releasing it only when I give the punch line.

That’s what you want to do in an introduction. You want to build on the reader’s interest in the subject by telling him a story about it. Every good story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. That is, it establishes a situation, introduces a complication, and offers a resolution. The resolution will always be your major point, since you always write either to resolve a problem or to answer a question already in the reader’s mind.

But the story has also got to be a good story for the reader. If you have any children you know that the best stories in the whole world are ones they already know. Consequently, if you want to tell the reader a really good story, you tell him one he already knows or could reasonably be expected to know if he’s at all well informed.

翻译

为什么要用故事?

仔细想想,你会明白,没人会像真正想读一本被所有人称赞为引人入胜、充满魅力的小说那样,真正想读你写的内容。他的脑海中早已充满了纷杂且无关的想法,大部分是关于其他主题的,并且对他而言这些想法都非常珍贵和有趣。要让他放下这些想法,仅关注你所提供的信息,而他对这些信息的兴趣并不强烈,这需要付出相当的努力。只有当有一个令人无法抗拒的吸引力时,他才会乐于付出这份努力。

即使他非常渴望知道你的文件内容,并且确信内容有趣,他仍然必须努力排除其他思绪,专注于你所说的内容。我们都经历过读了一页半的内容后突然意识到自己没理解其中一句话的情况。这是因为我们没有排除脑中已有的想法。

因此,你需要给读者提供一种“装置”,让他更容易放下其他想法,仅专注于你所说的内容。这种万无一失的“装置”就是一个未完的故事。例如,假设我对你说:

“两个爱尔兰人在午夜时分,在一座陌生城市的桥上相遇……”

此刻,我已经成功地引起了你的兴趣,不论你在读到这些话之前在想些什么。我将你的思绪锁定在一个特定的时间和地点上,通过集中你的注意力在这两个爱尔兰人所说或所做的事情上,有效地控制了你的思维,并且只有在我揭示故事的关键点时才放手。

这正是你在引言中想要做到的。你想通过一个关于主题的故事来激发读者的兴趣。每个好的故事都有一个开头、中间和结尾。也就是说,它建立了一个情境,引入了一个复杂情况,并提供了一个解决方案。这个解决方案将始终是你的主要观点,因为你写作的目的总是为了解决一个问题或回答一个已在读者脑海中的问题。

但这个故事还必须是一个好故事,对读者来说是有吸引力的。如果你有孩子,你就会知道全世界最好的故事是那些他们已经知道的。因此,如果你想讲一个真正吸引读者的好故事,你就要讲一个他们已经知道的故事,或者是一个如果他们信息充足就可以合理地知道的故事。

原文

Psychologically speaking, of course, this approach enables you to tell him things with which you know he will agree, prior to your telling him things with which he may disagree. Easy reading of agreeable points is apt to render him more receptive to your ideas than confused plodding through a morass of detail.

翻译

从心理学角度来说,这种方法让你可以先告诉读者他会同意的内容,再告诉他可能会有分歧的内容。轻松阅读这些让人认同的要点,往往能让他更容易接受你的观点,而不是在细节的迷雾中困惑地跋涉。

发表评论: